February 15, 2008

Los autonautas de la cosmopista

Ermita del Santo Calvario

March 21, 2018, Antigua Guatemala

屋須弘平 — 恒屋盛服 — 鳥居龍藏

Sato san

佐藤静雄(November 2014) / 観樂樓(岩手県一関市藤沢町)

Whenever I visited Fujisawa, I knew where I could stay…

Finally the six masters, the hacienda owners, gathered together. The Continental Colonization Company had the Koreans stand up and form themselves into lines. The hacendados walked around and pointed at people with their canes. They singled out those who looked strong and healthy first. Unconsciously, the Koreans straightened their backs. […] More hacendados continued to arrive into the next day. They did not comment on the workers, but simply chose the first ones they saw and took them to their haciendas. The Koreans from the Ilford were scattered among twenty-two haciendas in the Yucatán. It took a week for all 1,032 to be chosen. The last hacendado to arrive, a mestizo, appeared alone on a horse pulling a cart with no driver and no servants. He ran a hacienda near the Guatemala border. The representative of the Mérida association of hacendados pulled aside the tent flap, flashed him a smile, and went out to greet him. He brought with him a Korean man who had been squatting in the shade of a carriage to avoid the sun. “All the others have been taken, and only this one is left.” The representative smiled broadly, showing his teeth. The young mestizo had no choice, so he signed the document and looked at the last Korean. It looks like it’s time to hear a new song. The singing never ceased at his hacienda. He heard African songs from the blacks he had bought from Belize. He had Mayans, once the rulers of the Yucatán, singing Mayan songs. He had coolies singing the boat songs of Guangzhou. The mulattos from across the channel in Cuba were skilled in dancing and drumming. Now he would be able to hear strange new songs from this man who came from a place called Korea.

Kim Young-ha. 2013. Black Flower: A Novel. Translated by Charles La Shure. Mariner Books.

The old doctor felt my pulse, evidently thinking of something else the while. ‘Good, good for there,’ he mumbled, and then with a certain eagerness asked me whether I would let him measure my head. Rather surprised, I said Yes, when he produced a thing like calipers and got the dimensions back and front and every way, taking notes carefully. He was an unshaven little man in a threadbare coat like a gaberdine, with his feet in slippers, and I thought him a harmless fool. ‘I always ask leave, in the interests of science, to measure the crania of those going out there,’ he said. ‘And when they come back too?’ I asked. ‘Oh, I never see them,’ he remarked; ‘and, moreover, the changes take place inside, you know.’ He smiled, as if at some quiet joke. ‘So you are going out there. Famous. Interesting too.’ He gave me a searching glance, and made another note. ‘Ever any madness in your family?’ he asked, in a matter-of-fact tone. I felt very annoyed. ‘Is that question in the interests of science too?’ ‘It would be,’ he said, without taking notice of my irritation, ‘interesting for science to watch the mental changes of individuals, on the spot, but …’ ‘Are you an alienist?’ I interrupted. ‘Every doctor should be—a little,’ answered that original, imperturbably. ‘I have a little theory which you Messieurs who go out there must help me to prove. This is my share in the advantages my country shall reap from the possession of such a magnificent dependency. The mere wealth I leave to others. Pardon my questions, but you are the first Englishman coming under my observation …’ I hastened to assure him I was not in the least typical. ‘If I were,’ said I, ‘I wouldn’t be talking like this with you.’ ‘What you say is rather profound, and probably erroneous,’ he said, with a laugh. ‘Avoid irritation more than exposure to the sun. Adieu. How do you English say, eh? Goodbye. Ah! Goodbye. Adieu. In the tropics one must before everything keep calm.’ … He lifted a warning forefinger. … ‘Du calme, du calme. Adieu.

Joseph Conrad. 2002. Heart of Darkness and Other Tales. Edited by Cedric Thomas Watts. Oxford University Press.

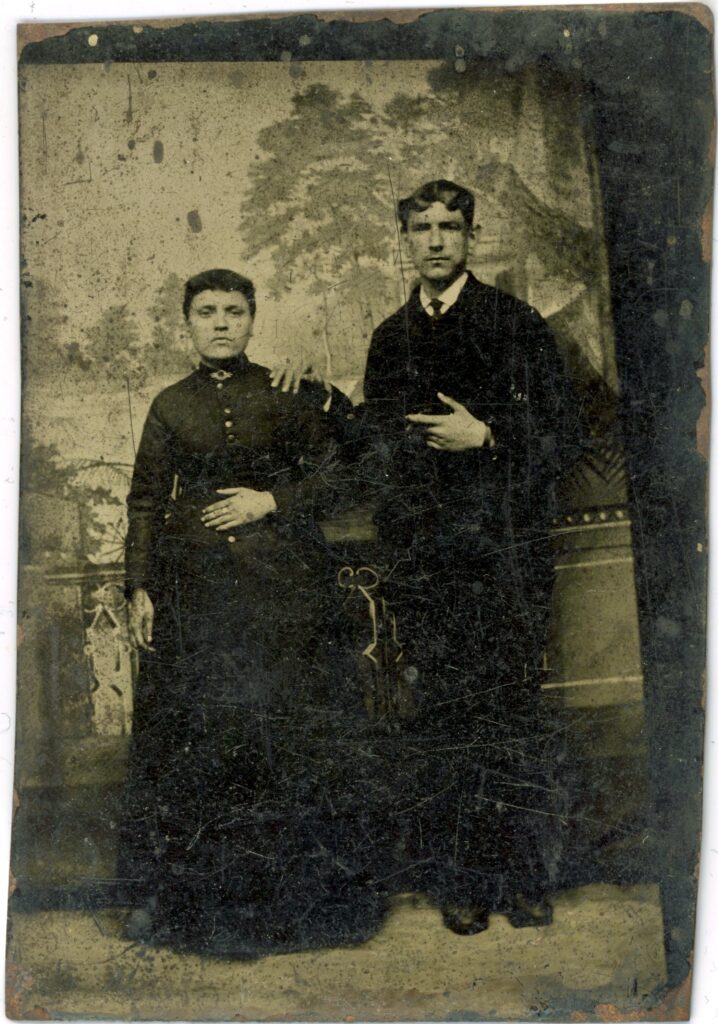

ferrotype

C/O Berlin

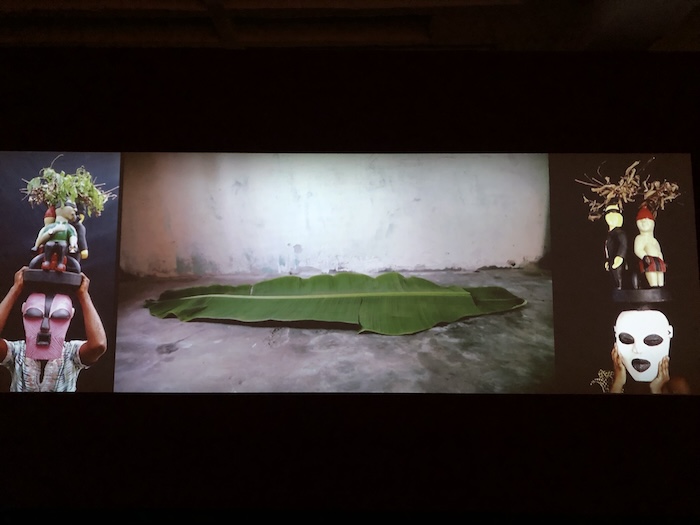

in this space we breathe, Khadija Saye

Worrying The Mask: The Politics of Authenticity and Contemporaneity in the Worlds of African Art (2020), Zina Saro-Wiwa

“Players take turns rolling two dice. One dice, numbered one to six, determines how many spaces a piece is moved on the board. The other dice determines a language and decides which player’s piece is moved. When a player rolls their assigned language, they read an excerpt from historical documents stored in the Togolese National Archives. These documents are letters or reports exchanged between missionaries and officials, focusing on linguistic issues in colonial Togo.” Protektorat, Silvia Rosi

Tümpel im Wald, an der Ostsee